The time that I’ve been dreading is upon me: I started my PhD qualifying exams this week. I took my written exam for Modern European History on Tuesday, and I’ll write my exam for the History of Sexuality on Monday. A week later, I’ll do my last written exam, in Modern German History. And then I’ll have two days to recoup and take my oral exams in front of all three professors at once.

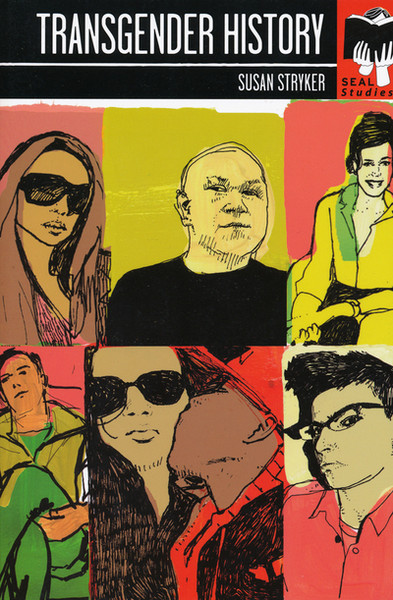

In order to prepare for these exams, I read 137 books and articles in the past 9 months and wrote a two-page summary of each one (that’s a picture of most of the books up there!). I’ve had a couple of professors tell me that you’ll know the most stuff that you’ll ever know during your reading/exam year. You’ll never read as broadly after that because you’ll just start specializing and defining your expertise in a random niche somewhere. After this reading year, I’m not even sure if I’m all that much smarter; I think my brain is just a little more fried is all.

Below is my book list. Some of them are hyperlinks to the book summary that I’ve posted in the past. If you want my opinion (or want to share yours!) on any of the books, let me know:

Modern European History

Session I: Contextualizing Europe

- Bayly, C.A. The Birth of the Modern World: 1780-1914, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003.

- Osterhammel, Jürgen and Niels P. Petersson. Globalization: A Short History, Princeton University Press, 2009.

Session II: Nationalism & Nation Building

- Waldstreicher, David. In the Midst of Perpetual Fetes: The Making of American Nationalism, 1776-1820. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997.

- Applegate, Celia. Bach in Berlin: Nation and Culture in Mendelssohn’s Revival of the St. Matthew Passion. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2005.

- Todorova, Maria. Imagining the Balkans. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Mazower, Mark. The Balkans: A Short History. New York: Modern Library, 2002.

Session III: Science & Society in the 19th Century

- Winter, Alison. Mesmerized: Powers of Mind in Victorian Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Geison, Gerald L. The Private Science of Louis Pasteur. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

- Kern, Stephen. The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918. With a new preface by Stephen Kern. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003.

Session IV: the “Fin-de-Siécle:” Culture & Society around 1900

- Schorske, Carl E. Fin-de-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. New York: Knopf, 1979.

- Coen, Deborah R. Vienna in the Age of Uncertainty: Science, Liberalism, and Private Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

- Schwartz, Vanessa R. Spectacular Realities: Early Mass Culture in Fin-de-Siècle Paris. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Eksteins, Modris. Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1989.

- Mosse, George L. Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Session V: European Mass Culture in the Context of Global War

- Manela, Erez. The Wilsonian Moment : Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Berghahn, Volker, R. Europe in the Era of two World Wars: From Militarism and Genocide to Civil Society. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2006.

- Andrews, James T. Science for the Masses: The Bolshevik State, Public Science, and the Popular Imagination in Soviet Russia, 1917-1934. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2003.

- Falasca-Zamponi, Simonetta, Fascist Spectacle: The Aesthetics of Power in Mussolini’s Italy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Session VI: Life Under Totalitarian Regimes

- Proctor, Robert. The Nazi War on Cancer. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1999.

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila. Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Session VII: Writing Modern European History

- Mazower, Mark. Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century. New York: Vintage, 2000.

- Wasserstein, Bernard. Barbarism and Civilization: A History of Europe in Our Time. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

Modern German History

I: Surveys & the Sonderweg

- James J. Sheehan, German History, 1770-1866

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler, Deutsche Gesellschaftsgeschichte, Volumes 1-5

- William Hager, German History in Modern Times: Four Lives of a Nation

- Friedrich Meinecke, the German Catastrophe

- David Blackbourn and Geoff Eley, Peculiarities Of German History

II: The German Question

- Thomas Nipperdey, Germany From Napoleon to Bismarck

- Matthew Levinger, Enlightened Nationalism: the Transformation of Prussian Political Culture, 1806-1848

- Lother Gall, Bismarck: Der weisse Revolutionär

- Jonathan Sperber, Rhineland Radicals: The Democratic Movement and the Revolution of 1848-1849

- Celia Applegate, A Nation of Provincials: The German Idea of Heimat

III: The Nature of the Kaiserreich

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler, the German Empire 1871-1918

- Vernon Lidtke, The Alternative Culture: Socialist Labor in Imperial Germany

- Geoff Eley, Reshaping the German Right: Radical Nationalism and Political Change after Bismarck

- Helmut Walser Smith, German Nationalism & Religious Conflict: Culture, Ideology, Politics, 1870-1914

- Margaret Anderson, Practicing Democracy: Elections and Political Culture in Imperial Germany

- Lora Wildenthal, German Women for Empire, 1884-1945

IV: World War One

- Roger Chickering, Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914-1918

- Isabel Hull, Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany

- Paul Lerner, Hysterical Men: Wary, Psychiatry, and the Politics of Trauma in Germany, 1890-1930

- Fritz Fischer, Germany’s Aims in the First World War

- Belinda Davis, Home Fires Burning: Food, Politics, and Everyday Life in World War I Berlin

V: Weimar

- Eric Weitz, Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy

- Detlev Peukert, the Weimar Republic

- Maria Tatar, Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany

- Klaus Theleweit, Male Fantasies, Vol 1

- Martin Broszat, Hitler and the Collapse of Weimar Germany

VI: Nazi Germany

- Robert Gellately, Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler (both volumes)

- Detlev Peukert, Inside Nazi Germany: Conformity, Opposition, and Racism in Everyday Life

- Claudia Koonz, Mothers in the Fatherland: Women, the Family and Nazi Politics

- Karl Bracher, The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Effects of National Socialism

- Martin Broszat, The Hitler State: The Foundation and Development of the Internal Structure of the Third Reich

VII: After 1945

- Herman Weber, Geschichte der DDR

- Eckart Conze, Die Suche nach Sicherheit

- Uta Poigert, Jazz, Rock, and Rebels: Cold War Politics and American Culture in Divided Germany

- Konrad Jarausch & Michael Geyer, Shattered Past: Reconstructing German Histories

- Jeffrey Herf, Divided Memory: the Nazi Past in the Two Germanys

- Richard Evans, “The New Nationalism and the Old History: Perspectives on the West German Historikerstreit” in The Journal of Modern History. Vol. 59, No. 4 (Dec. 1987): 761-797

VIII: History of Jews in Germany

- Jacob Katz, Out of the Ghetto: the Social Background of Jewish Emancipation, 1770-1870

- Marion Kaplan, the Making of the Jewish Middle Class: Women, Family, and Identity in Imperial Germany

- Christopher Browning, Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland

- Raul Hilberg, the Destruction of the European Jews (3 Volumes)

- Henry Friedlander, the Origins of Nazi Genocide: From Euthanasia to the Final Solution

The History of Sexuality

I: Theory

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality V. 1: An Introduction, (1990)

- Katz, Jonathan Ned. The Invention of Heterosexuality (1995)

- Sedgwick, Eve. Epistemology of the Closet (1991)

- Halperin, David. “Forgetting Foucault,” Representations, No. 63 (Summer, 1998): 93-120.

- Weeks, Jeffrey. “Remembering Foucault,” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 14, No. 1/2, (January/April 2005): 186-201.

- Halperin, David. How to Do the History of Homosexuality (2004)

- Stoler, Ann Laura. Race and the Education of Desire: Foucault’s History of Sexuality and the Colonial Order of Things (1995)

- McClintock, Anne. Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest, (1995)

- Rubin, Gayle. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality” in Carole Vance, Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality (1993)

- Scott, Joan. Gender and the Politics of History (1999)

- Angelides, Martin. A History of Bisexuality (2001)

II: General Overviews

- Duberman, Martin, Martha Vicinus, & George Chauncey, eds., Hidden from History: Reclaiming the Gay and Lesbian Past (1989)

- Abelove, Henry, Michele Barale, & David Halperin, eds., The Lesbian and Gay Studies Reader (1993)

- Rosario, Vernon A. ed., Science and Homosexualities, (1997)

- Rupp, Leila. Sapphistries: A Global History of Love between Women (2009)

- Plummer, D. One of the Boys: Masculinity, Homophobia, and Modern Manhood, (Harrington Park Press: 1999).

- Stryker, Susan. Trangender History (Seal Press, 2008).

- Lancaster, Roger N. The Trouble with Nature: Sex in Science and Popular Culture (2003)

- Laqueur, Thomas, “Orgasm, Generation, and the Politics of Reproductive Biology,” in Thomas Laqueur, ed., The Making of the Modern Body: Sexuality and Society in the Nineteenth Century (University of California Press, 1987).

- Boyd, Nan Alamilla and Horacio N. Roque Ramierez, eds. Bodies of Evidence: the Practice of Queer Oral History, Oxford Oral History Series, 2012.

III: European Sexuality

- Herzog, Dagmar. Sexuality in Europe: a Twentieth-Century History (2011)

- Houlbrook, Matt. Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957 (2006)

- Walkowitz, Judith R. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (1992)

- Clark, Anna. Desire: A History of European Sexuality (2008)

- Healey, Dan. Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia: The Regulation of Sexual and Gender Dissent (2001)

- Vicinus, Martha. Intimate Friends: Women Who Loved Women, 1778-1928 (2006)

- Trumbach, Randolph. Sex and the Gender Revolution: Heterosexuality and the Third Gender in Enlightenment London, (1998)

- Mosse, George L. Nationalism and Sexuality: Respectability and Abnormal Sexuality in Modern Europe, (1985)

- Marcus, Sharon. Between Women: Friendship, Desire, and Marriage in Victorian England (Princeton, 2007).

- Tampagne, Florence. A History of Homosexuality in Europe: Berlin, London, Paris, 1919-1939 (2004)

- Ruehl, Sonja “Inverts and Experts” in Judith Newton & Deborah Rosenfelt, eds., Feminist Criticism & Social Change: Sex, Class, and Race in Literature

- Boswell, John. Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality, (1980)

- Martel, Frédéric. The Pink and the Black: Homosexuals in France Since 1968 (1999)

- Gunther, Scott. The Elastic Closet: A History of Homosexuality in France, 1942-Present (2009)

- Bunzl, Matti. Jews & Queers: Symptoms of Modernity in Late Twentieth Century Vienna

IV: German Sexuality

- Fenemore, Mark. “The Recent Historiography of Sexuality in Twentieth-Century Germany” in The Historical Journal, Vol. 52, Issue 03, (Sept. 2009): 763-779.

- Spector, Scott, Helmut Puff, and Dagmar Herzog, eds. After the History of Sexuality (2012)

- Jensen, Erik. Body by Weimar: Athletes, Gender, and German Modernity (2010)

- Crouthamel, Jason. “Male Sexuality and Psychological Trauma: Soldiers and Sexual Disorder in World War I and Weimar Germany.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 17, no. 1 (January 2008): 60-84.

- Fout, John C. “Sexual Politics in Wilhelmine Germany: The Male Gender Crisis, Moral Purity and Homophobia.” In Forbidden History: The State, Society, and the Regulation of Sexuality in Modern Europe, edited by John C. Fout, 259-92, (1992)

- Giles, Geoffrey J. “The Institution of Homosexual Panic in the Third Reich.” In Social Outsiders in Nazi Germany, edited by Robert Gellately & Nathan Stoltzfus (2001)

- Heineman, Elizabeth D. What Difference Does a Husband Make: Women and Marital Status in Nazi and Postwar Germany (1999).

- Koonz, Claudia. Mothers in the Fatherland. Women, the Family, and Nazi Politics (1986)

- Herzog, Dagmar. Sex after Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth-Century Germany (2007).

- Whisnant, Clayton J. Male Homosexuality in West Germany: Between Persecution and Freedom, 1945-69 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2012).

V: US American Sexuality

- D’Emilio, John & Estelle Freedman, Intimate Matters: A History of Sexuality in America. Third Edition (University of Chicago: 2012)

- Berube, Allan. Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two (2000)

- Duggan, Lisa. “The Trials of Alice Mitchell: Sensationalism, Sexology, and the Lesbian Subject in Turn-of-the-Century America,” Signs 18 (Summer 1993).

- Faderman, Lillian. Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-century America, (1991)

- Johnson, David K. The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government (2006)

- Meyerowitz, Joanne. How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States (2004)

- Rupp, Leila. A Desired Past: A Short History of Same Sex Love in America, (2001)

- Somerville, Siobhan B. “Scientific Racism & the Emergence of the Homosexual Body” in the Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 5, No. 2. (Oct., 1994): 243-266

- Stryker, Susan. Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback, (2001)

- Amrstrong, E., Forging Gay Identities: Organizing Sexuality in San Francisco, 1950-1994, (University of Chicago: 2002).

- Kevin Mumford, Interzones: Black/White Sex Districts in Chicago and New York in the Early Twentieth Century (1997)

- Chad Heap, Slumming: Sexual and Racial Encounters in American Nightlife, 1885-1940 (2010)

- Chauncey, George. Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (1995)

- Kennedy, Elizabeth and Madeline Davis. Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community, (1993)

- Johnson, Patrick. Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South, (2008)

VI: Gay Rights Movements in the US

- Stein, Marc. Rethinking the Gay & Lesbian Movement, (Routledge, 2012).

- Canaday, Margot. The Straight State: Sexuality and Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America, (Princeton Press, 2009)

- D’Emilio, John. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940-1970, (1983)

- Meeker, Martin. “Behind the Mask of Respectability: Reconsidering the Mattachine Society and the Male Homophile Practice, 1950s and 1960s.” Journal of the History of Sexuality, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Jan. 2001): 78-116.

- Brandt, Eric. Dangerous Liaisons: Blacks & Gays and the Struggle for Equality, (New Press: 1999).

- Armstrong, Elizabeth & S.M. Crage. “Movements and Memory: The Making of the Stonewall Myth,” in American Sociological Review Vol. 71, No. 5 (2006): 724-751.

- Avila-Saavedra, G. The Construction of Queer Memory: Media Coverage of Stonewall 25. Paper delivered at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, San Francisco. Accessed at http://list.mseu.edu/cgi-bin/wa?A2=ind0610d&L=aejmc&P=2281

- Chasin, Alexandra. Selling Out: The Gay and Lesbian Movement Goes to Market (Palgrave, 2000).

- Gallo, Marcia, Different Daughters: A History of the Daughters of Bilitis and the Rise of the Lesbian Rights Movement, (Carroll & Graf: 2006).

- White, Todd. Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social History of the Movement for Homosexual Rights (University of Illinois, 2009).

Just for Fun

I did get a chance – usually on the bus and train on the way to work and back home – to read some novels just for fun:

- The Stand by Stephen King

- The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett

- Habibi by Craig Thompson (the first graphic novel I’ve read – it was fantastic)

- The Casual Vacancy by J. K. Rowling (one of the most depressing and upsetting things I’ve ever read)

- Dream Boy by Jim Grimsley

- 2312 by Kim Stanley Robinson (I started this one and trudged on until I was about halfway through, but then I did something that I’ve never done before: stopped reading it half-way through. Just that bad.)

- Where Things Come Back by John Corey Whaley (this was his debut novel, and I really enjoyed it)

- Eden at the Edge of Midnight by John Kerry

- Seraphina by Rachel Hartman (I’m in the middle of this one now and am loving it!)