Kindess: Let Me Do It Now

Show Compassion, Don’t Let Extremism Win

The past five days have been extremely emotional. It started with the horrific terror attacks in Paris that overshadowed a slew of other coordinated violence and natural disasters across the globe. But, it didn’t stop there.

Since then, my Facebook feed has become filled with a stream of animosity and hatred that is primarily fueled, I think, by a deeply emotional and irrational reaction to terror attacks on Western soil. When you add a dose of ignorance (that is, an absence of facts or logic) to the mix, you get a dangerous concoction of arrogance, aggression, and xenophobia.

It makes me wonder: Have we learned nothing from 9/11? In the days and months following that September day, Americans were horrified, angry, and scared. We allowed a deceitful administration to lie to us and talk us into launching not one, but two wars. And the truth of the matter was, we didn’t need much convincing. We were craving vengeance, revenge, justice…anything. But, we’ve now seen what happens when we make such important decisions based on emotional, knee-jerk reactions. The same thing is happening now in the wake of the Paris attacks. People clamor for more war while we let our fears dictate our reactions….And this is exactly what the terrorists want.

So, I want to take a moment to address some of the things that I’ve seen making their way through the Facebook universe, and offer a historian’s thoughts on the situation.

Be smart; don’t click “share” without first checking to see if it’s true. I think this is the first step to addressing the tide of fear and hatred. Just because someone on Facebook shares something from a random website or blog, that doesn’t make it true. In fact, a lot of the stuff I’ve seen out there is just simply wrong, false, inaccurate, fake, deceitful, incorrect, fictitious, misleading. Take the following picture for example:

These are supposedly Muslim women here in the USA protesting for the downfall of our country. A simple Google search, however, reveals that these are actually women in Iran.

The caption reads (at least in one of its variations) that these are Muslim women HERE in America showing their “appreciation” for American freedom by writing “Down with USA!” on their hands. When I saw this, I was shocked, and thought, if this is true, it is certainly absurd and infuriating. BUT, instead of clicking “like” or “share,” I simply opened a new tab and Googled “muslim women America down with usa on hands.” ALL of the results on the front page easily and quickly revealed that this picture is actually from Iran, NOT America. Mind you, as a historian I have years of experience doing hardcore, extensive archival research on complex topics. But you don’t need all that to confront such blind, ignorant bigotry. All you need is Google. So, PLEASE do humanity a favor and do some basic fact checking before you contribute to the spread of falsities and hatred.

The claim that President Obama is weak on ISIS. Of course, this sentiment is driven by political allegiances. Obama is not a gun-toting tough guy who sounds like he’s from the Wild West, using phrases like “dead or alive” and “smoke them out” of their holes… so, he must be weak, right? After the Paris attacks, France lead a series of airstrikes against ISIS targets, and I saw people shouting (or, the caps-lock equivalent thereof): WHY AREN’T WE DOING ANYTHING?!

Well, here are some numbers for you to put some things into perspective: According to statistics just released by the U.S. Department of Defense, in the last 15 months, President Obama has authorized 6,353 airstrikes against ISIS. All of the other 12 coalition countries combined have launched 1,772 strikes. That means that 78% of the bombs being dropped on ISIS are American. So, Obama leads more than 3 out of 4 of the attacks against ISIS, and yet his opponents are still claiming that he is weak, taking a back seat?! The extreme right-wingers even go as far to say that this “reveals” that he’s not-so-secretly a Muslim terrorist himself. Give me a break. Get your facts straight instead of mouthing off about things you don’t understand. And whether you want to believe that President Obama is weak or not, the fact remains that we are still leading the fight against ISIS – by a large margin. And the pesky thing about facts is that they remain true whether you choose to believe them or not.

Refusing to take Syrian refugees. I want to express my thoughts on this in length, because as I’ve said before, I believe that the treatment of Syrian refugees is not a political issue – it is a test of our moral fortitude. But first, I want to get a few facts out there:

(1) No one is suggesting that we just throw open our borders and let people from Syria just run across and do whatever they want to. Did you know that the vetting process to obtain refugee status in the United States is one of the toughest in the world? In many cases, it is more difficult for a refugee fleeing war to be allowed into the country than it is for someone to get a student visa to come attend college. As it is now, America’s vetting process for refugees takes TWO YEARS and involves multiple international organizations. First, refugees must go through 2 interviews at the United Nations; then, they are fact checked by three US government departments, including the State Department, the Department of Homeland Security, and the FBI. That’s just for the normal, everyday people. If, at any time, a red flag goes up, they go through a lot more. This vetting process has an EXCELLENT track record. The United States has taken in 784,000 refugees since 2001. None of them have carried out attacks. It’s not 100% fool-proof, mind you; nothing can be. Out of those 784,000, three men have been arrested under suspicion of potential involvement in terrorist activities. That means, that out of all the refugees we’ve taken in during the last 14 years, exactly 0.0000038% wanted to (potentially) do America harm – – AND WE CAUGHT THEM. That’s the thing about these refugees. They’re in the system; the government keeps closer tabs on them than any of the rest of us. (And, no the Tsarnaev brothers [the Boston Marathon Bombers] were not “refugees.” Their family came over under the protection of political asylum, which is different.)

(2) There is a particularly ignorant idea that I’ve seen floating around Facebook…and it goes a little something like this: “Why are all the Syrian refugees men?!?! They’re sending over their men as an invasion! Wake Up America!!” Really, I’m not sure how ignorant and scared you must be to believe this line of “reasoning.” The Syrian Civil War has been going on for over four years, and of course when a family decides that there is no future for them in their home country and that they must make the hard decision to leave, the father or oldest brother will go first – not to invade Western countries, but to find a place to live, to establish a little bit of stability so that when he calls for his family to come, they’re not all living on the street or worried about how to survive. THAT is why men came first. But now that the war has gotten so incredibly horrible, entire families leave everything they’ve ever known, and pay bandits to help them pile onto a boat and flee the constant danger. Now there is no time for men to go first; everyone has to flee as soon as possible;

(3) Syrians aren’t “looking for a better life.” That’s incredibly naive and degrading. The VAST majority of these Syrians would choose to stay in their home country, given the chance. They’re not looking for a free ride on American welfare; they’re not wanting riches and endless possibilities in the US of A. They’re not simply looking for a “better” life. They’re just hoping to live. Period. They want to be able to wake up and see another sunrise. Do you want to know why they’re risking their lives to cross open seas and walk across entire nations? Take the horrors of Paris on November 13, 2015. And now imagine that is your life EVERY.SINGLE.DAY. That is what these people are fleeing. The fear that they, or their children may suddenly be BLOWN UP, reduced to ragged pieces of flesh or pink mist. And it’s not only one set of bombers that they have to fear: They get to worry about whether it will be their own government killing them, or if it’ll be Russian jets, American drones, or ISIS suicide bombers. Everywhere they look, there is only death.

(4) There is a mindset that we shouldn’t “take care of” anyone else until there is no poverty or hunger in America. In other words, this argument states that somehow these refugees will be getting money that would otherwise be going to feed starving children or homeless veterans. This is simply an illogical, gut-response argument that isn’t based on knowledge of the facts. There are starving children and homeless veterans for a number of political reasons that I don’t have the time or effort go to into here. We are the richest nation in the history of the world; we COULD pay for every single person in our country AND every single refugee if we wanted to. But we don’t. It’s not that we CAN’T pay for our own; we don’t. This problem has nothing to do with the refugees. (Not to mention that refugees wouldn’t simply be getting a check and living off of our government, so their lives wouldn’t cost us a whole lot…Don’t worry.)

(5) All of these governors who are vowing to refuse any and all Syrian refugees…Guess what – you have no legal authority to do that. You don’t have a legal leg to stand on. The Refugee Act of 1980 gives broad, discretionary powers to the President of the United States to accept and handle refugees.

***

I’ll end with my thoughts on the morals and ethics at play here. Because, it’s easy to get bogged down in the political fights of numbers, statistics, jabs, lies, and sound bytes. We forget that, at the heart of all of this, are people. Human lives. Mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, children. All of whom have fears of their own, along with things that bring them joy; people who have just one life to live – and this is it.

The United States of American is a country of immigrants. We are made stronger, not weaker, by our cultural, religious, ethnic, sexual, and racial diversity. We constantly think of ourselves as a moral leader in the world, the “beacon of hope” that stands for freedom and compassion and acceptance. There is a plaque on the Statue of Liberty that reads: Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore. Send these, the homeless, tempest-tossed to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

What is it that we actually stand for?

If we shut our doors to these Syrians whose homes and lives have been destroyed, then we are betraying everything that we as Americans proclaim to stand for. I was horrified to learn that Jeb Bush and Ted Cruz believe that America should only let in Christian refugees! These men want to become the next President, and they believe that some lives are more worthy of saving just because they adhere to one particular religion over another. There is no religious test for true compassion. In fact, that’s the definition of compassion – it’s a sympathy and concern for the suffering of others based on their common humanity, nothing else.

Moreover, the people who are screaming and clamoring to keep the Syrians out are the same ones who claim to be “Pro-Life” – who shout that “All Lives Matter!” So, the lives of unborn fetuses matter more to you than the refugee children and mothers and fathers who seek safety and life? Is it because the “life” that you so desperately defend is white and “Christian” (even though it’s unborn and hasn’t had the chance to choose a religion yet)?

And for those of you who use religion as a way to justify the ignoring of Muslim suffering, I suggest you read your own Bible. Take, for example, Leviticus 19:33-34: “When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were once foreigners in Egypt. I am the Lord your God.” Or how about Matthew 25:41-46:

“”Then he will say to those on his left, “Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For, I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not love after me.” They will answer, “Lord, when did we see you hungry or thirsty or a stranger needing clothes or sick or in prison, and did not help you?” He will reply, “Truly, I tell you, whatever you did not do for one of the least of these, you did not do for me.” Then they will go away to eternal punishment, but the righteous to eternal life.”

I came across this disgusting, repulsive picture this morning:

The Facebook caption reads: “Can you tell me which of these rattlers won’t bite you? Sure some of them won’t, but tell me which ones so we can bring them into the house.”

It compares all Syrian refugees to rattlesnakes. It dehumanizes them, robs them of their very humanity as a way to justify Islamaphobia and xenophobia. You can have compassion for a human, but you can’t have compassion for a rattlesnake. Funny thing though, the Nazis dehumanized the Jews. They called them rats, vermin, a plague. It made it easier for the Germans to gas the Jews if they didn’t see the Jews as human. It makes the decision to ignore the suffering of Syrian refugees if you don’t think of them as humans.

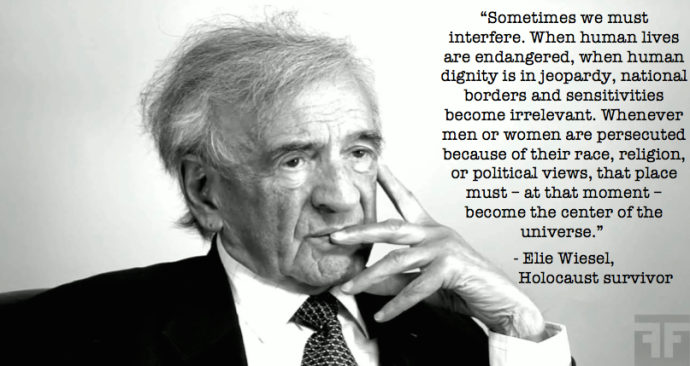

I understand that much of the fear of terrorist attacks is justified. But, we shouldn’t let that fear drive us to devolve to a point that we ignore the fact that the same terror and same enemy that we face is also what these Syrian refugees are fleeing from…only their fears aren’t of potential attacks to come in the future. They are fleeing from daily war. One of our greatest founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin once said: “Those who would give up essential Liberty to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety.” I think this applies to our current situation as well. We can not be willing to sacrifice our values (which include sharing liberty with others) just out of fear for safety. Otherwise, there is nothing that makes America exceptional. Otherwise, we are nothing but a large group of people who are only interested in ourselves. “Freedom should never be at the expense of someone who has no freedom.” Elie Wiesel said that. He’s a Holocaust survivor, so he knows something about human nature and the fragile existence of freedom and life. We should never purchase our freedom by denying it to others. But, luckily, compassion, the value of all human life, and national security are NOT mutually exclusive. We can still be a shining beacon of hope to those fleeing warfare and death AND keep ourselves safe. We just have to double down on our security efforts while also taking a breath and pausing to remember what it is we stand for before we make drastic decisions.

Do you want to know the ironic thing? This reaction is exactly what ISIS wants. Having 30 or so US Governors declare that there is no room for Muslim refugees…Having millions of Americans (and other Westerners) spew anti-Muslim hatred on social media…It’s the perfect propaganda for the ISIS cause. They will be able to say: See, the West hates Muslims! When anything goes wrong, they show their true nature! ISIS leaders have made this goal clear, stating in January that they hope their endless string of attacks on Western civilians would “compel the Crusaders to actively destroy the grayzone themselves.” In other words, they’re hoping that Western government and civilians will react violently, over generalize, and destroy the “grayzone” of the world, creating an oversimplified worldview where the West = Good; and Muslims = Evil. ISIS is hoping that innocent Muslims will become the victims of discrimination, bigotry, even violence. This will only drive others to become radicalized and join the ISIS cause. In other words, ISIS is setting a trap for the West, and we’re walking right into it.

So, if we forsake our American values, our belief that “all men are created equal,” and give in to base, animalistic emotions and fears…then the terrorist win. Then, they have transformed us into a nation that is willing to declare that some lives are worth more than others, and that we don’t think rationally, and don’t even care to. We have to destroy the threat caused by ISIS and international terrorism, but we shouldn’t forfeit our values and sell our souls to do so.

The Center of the Universe

Refugees and the Test of Morality

Gustav Schroeder, Cptt. of the St. Louis. Photo Courtesy of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

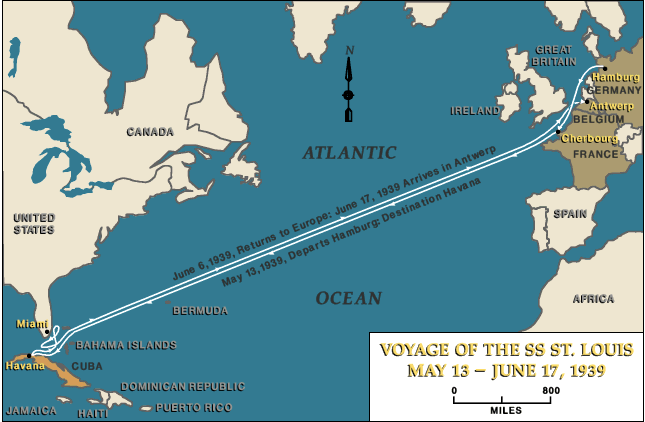

I visited the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. this past weekend, and one part of the permanent exhibit stood out to me. It was the story of the German transatlantic liner, the St. Louis. In May 1939, it sailed from Germany to Cuba with 937 passengers, most of them Jewish refugees fleeing the escalating violence in Nazi Germany. The passengers had been granted visas to Cuba; however, when the ship arrived, only 28 people were let off. The remainder were told to go home.

The ship then sailed northwards, hoping that the United States would provide refuge. But, the President, State Department, and Congress all denied aid to the passengers of the St. Louis. They were close enough to Florida to see the city lights of Miami, but were not allowed to dock. The “Land of the Free” was dedicated to “staying out of world affairs” and many Congressional leaders worried that letting in a flood of refugees would hurt the U.S. economy.

The St. Louis was forced to return to Europe. Several European countries agreed to take in the refugees, but within a short time, Hitler’s Blitzkrieg engulfed Europe in war and brought much of the continent under Nazi control.

Of the St. Louis’ 937 passengers, 284 were ultimately killed in the Holocaust.

As I stood and read the story of the St. Louis, I couldn’t help but think about the masses of Syrian refugees fleeing civil war and almost certain death in their home country. They have left everything they know and love behind and are asking someone to help them.

Whether or not we are doing ALL that we can to help these people is not an economic or political question, it is a MORAL question; it is a test of ethics. As the case of the St. Louis shows, it’s a test that we have failed before…Are we going to learn from our mistakes, or is someone 70 years from now going to sit and judge us for not doing more?

Remember that these refugees aren’t just numbers; they’re all human beings with worries, fears, hopes, and joys. The majority aren’t just “seeking a better life;” they’re simply looking for a way to survive, to make sure that their children don’t die in a bomb explosion.

Migrants stand in a field as they wait for buses, after crossing the border from Serbia, near Tovarnik, Croatia September 24, 2015. Photo: REUTERS/Marko Djurica.

~*~*~*~*~

If you’re wondering how you can help the 4 million Syrian refugees in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq and Egypt you can donate to any of these charities:

The UN Refugee Agency: Provides cash for medicine and food, stoves and fuel for heating, insulation for tents, thermal blankets and winter clothing.

Save the Children: Supplies food for Syrian kids and supports education in Syrian refugee camps.

Médecins Sans Frontières/Doctors Without Borders: MSF is operating three rescue ships in the Mediterranean Sea that can carry hundreds of people to land.

Unicef: Delivers vaccines, winter clothes and food for children in Syria and neighboring countries. The agency is working to immunize more than 22 million children in the region following a polio outbreak.

International Rescue Committee: The group’s emergency team is in Greece, where nearly 1,000 people are arriving per day. Founded in 1933 at the request of Albert Einstein.

World Food Programme: The agency says it is struggling to meet the urgent food needs of millions of displaced Syrians.

Mercy Corps: Refugees are most in need of clean water, sanitation services, temporary shelter and food, the agency says.

Aylan Kurdi & Syria’s Child Victims of War: A new fund named after Aylan himself. Money goes to “Hand In Hand For Syria,” a U.K. based organization that works with the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

CARE: Reaches Syrian refugees in Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, Egypt, Yemen and those displaced inside Syria with food, hygiene items and emergency cash. It’s also helping refugees crossing into Serbia.

Traveling In Your Own Back Yard

Like many people, my family and I were shocked and saddened to learn that Mr. Jimmy Carter, the 39th President of the United States, has cancer. It shouldn’t have come as much of a surprise since so many of his relatives died of cancer, but still…

The 90 year-old seems to be handling the diagnosis and first round of treatment with a good humor; he was nothing but smiles when he held the press conference to let everyone know.

Mr. Carter grew up in Plains, Georgia, which is just a hop, skip, and a jump away from where I grew up. We all knew that he regularly taught Sunday School lessons at his church when he was home and not away advocating for women’s rights or building homes for the impoverished all across the globe, and just generally practicing what he preaches. But, we never made the short drive to attend one of these lessons until I was 24. (I had spent that summer home from grad school, and after months of eating my mom’s and grandma’s home cooking, I could no longer button my only pair of nice pants. So, I had to go meet the former president with my pants undone, nothing but my belt holding them up. I wrote about it HERE.)

Since that first trip, I had visited again, and my family had gone a couple more times. I started reading An Hour Before Daylight, Carter’s memoirs about his childhood, a couple of months ago, and we’ve all been talking about taking another Sunday trip over to Plains. So, we decided to go this past weekend. We normally show up at the church around 8:30 or 8:45am for Sunday School to start at 10, but we knew that we should probably get there a little extra early this time. So, we got there at 8:00, thinking that was “early.” Boy, were we wrong! People had camped out the night before, and they had to open up the Plains High School as an overflow space for the hundreds of people who couldn’t fit in the church.

That’s where we were directed. But even with this new space, we had come too late. Nearly 450 had fit into the church itself, and the high school building down the street could fit another 250. But we were around #275 in that line, so we were unfortunately turned away…along with about 250 other people. Of course it was a little disappointing, but I really felt bad for the people who had driven so far and yet didn’t get to hear Mr. Jimmy speak.

But, I’ll say that it was simply heartwarming to see such support for the Carters. People had driven from far and wide not only to hear his spiritual lesson, but to let him and his family know that their thoughts are with them.

When the secret service agent let us know where the cut-off would be for admittance into the high school, not a single person groaned, complained or made a scene. Everyone said, “That’s okay, we understand.” I later told one of the organizers: “Of course, we were all a little disappointed, but please just let Pres. Carter know how many people showed up to support him.”

But of course, he knows. In fact, this was the first time in the three decades that he’s been teaching Sunday School that they’ve had such a crowd; no one was prepared for it. Sunday morning, when they realized that there were way, way too many people to fit in the church sanctuary, Mr. Carter said, “Okay, open up the high school, and I’ll go down there and give a second Sunday School lesson to them.” He could have said – What is this? This is not a spectacle or a campaign rally; it’s my personal worship service. But instead, he accommodated as many people as possible.

He’s said that he’ll keep teaching Sunday School as long as he’s physically and mentally able. Bless his sweet, compassionate heart.

~*o0o*~

On my way back to Atlanta, I began noticing signs for the Andersonville National Historic Site. Again, this was only about 30 minutes from my house, but I had never visited. So I pulled in and spent about half an hour driving around the park and reading the placards about the former prisoner of war camp. They had marked out the perimeter of the prison walls, and as you stood overlooking the rolling hills below, you could really imagine how large of a prison camp it was. I couldn’t believe that none of our history teachers had brought us there on a field trip.

The National Park Service has recreated some of the pieces of the prison cap walls to give visitors an idea of what it looked like.

It’s strange how much of an effect time and maturity can have on a person. I’m a historian and I spent 15 years growing up a short drive from so many historical sites: the home place of a US President, the Andersonville site, Selma-Alabama, numerous Native American sites. The only one I remember visiting with any regularity is Westville, a living museum that recreates the daily life of those from the 1850s. But now, I realize how much of a treasure it is to have had these things so close by.

It was nice to take some of the back roads home. Instead of being inundated by the interstate billboards and strip malls, I got to roll my windows down and take in the beauty of southwest Georgia’s rural countryside. It’s scenery that I saw every single day for years…and never thought that there was anything particularly beautiful about it. But, once you’re gone and spend time surrounded by asphalt and concrete, the rolling green hills seem more liberating…not quite as confining as they seemed to a restless teenager.

Of course, this landscape only appears to be “natural.” There’s nothing natural about the tidy pecan orchards or the hundreds of acres of crops, all neatly aligned. Even the pine tree forests are arranged in perfectly straight rows. The fields that aren’t planted in cotton at the moment are tilled up or mowed nice and neat. This isn’t natural, untouched wilderness; this land has been put under the yoke of agriculture. But still, it’s pretty.

A few years of age can change your perspective. It can turn a drive down ordinary, everyday back roads into a trip, a chance to do some traveling, even if it’s in your own back yard.

A Curious Wanderer is on Facebook!

Good morning everybody!

The Curious Wanderer is now on Facebook!

Life has gotten pretty hectic the past several months, and between writing a dissertation and now composing job application materials, I have very little time and effort left to past anything substantial here on this site. (And when I do find some time to sit down an click “Add New Post,” the obnoxious voice of guilt screams in my head “You could be spending this time on your dissertation! YOU SHOULD BE SPENDING THIS TIME ON YOUR DISSERTATION!”).

So, I decided to create a CW Facebook page. It’ll be easier and and quicker to share shorter ideas, thoughts and links there. Also, I think it’ll reach a different audience. But, that doesn’t mean that I’ll be abandoning this blog. I’m still going to post here as often as I can, but if you’d like to add some humanism, history, travelling, or love of food to your Facebook feed, head on over to facebook.com/acuriouswanderer and give the page a “Like”!

See you there!

Book Recommendations

It seems like all I do is read…Sometimes I think my eyes are going to fall out of their sockets as I just go insane. But, then again, I guess all that reading makes sense since I’m a historian (or maybe being insane make sense since I’m a historian?) Either way – sane or not – I am fortunate that I do get to read so much. Reading is a way to travel (even time travel!) to different epochs or far away worlds without ever leaving your doorstep. Sometimes the places you go to aren’t so pretty (my dissertation explores different Holocaust memories), but other times, the words of others are just inspiring.

Most of my day is spent frantically reading through old newspaper articles, diary entries, other snippets from the archives, and stacks of history books. But I try to keep a good balance of things I read: In the morning, I read non-fiction. During the day, it’s history research. And at night, I read from a novel before going to sleep. So, on any given day, I’m reading three different books, but as odd as it sounds, it’s a good way to keep myself sane! I’ve shared many of my reviews of academic books, but this morning I wanted to share a few titles of the books I’ve recently read that have nothing to do with my research.

*~*~*

Every morning, after I catch up on the daily news and water our garden and flowers, I enjoy my last cup of coffee with a good, non-fiction book. It’s my way of preparing myself for the day and trying to learn something new that doesn’t have anything to do with my research.

For the past year, I slowly made my way through Bill Bryson’s A Short History of Nearly Everything. It’s a mammoth of a book that begins literally at the beginning of the time by exploring theories about the beginning of the universe and ends with the emergence of Homo sapiens. In between, Bryson deftly leads readers through some (most? all?) of the major scientific developments in human history.

The amount of research required to write such a book is simply staggering, but Bryson’s major achievement, in my opinion, is the way that he weaves it all together into a narrative that is simultaneously educational and incredibly entertaining. More than once I found myself laughing out loud as he let you in on some of the more obscure – and often absurd – secrets about the quirky personalities of the explorers, scientists, and curious amateurs who made significant (or not so significant) achievements in various fields. But, of course, beyond entertaining you, Bryson teaches you something, as well. After completing the book, I certainly feel more prepared on trivia nights!

The amount of research required to write such a book is simply staggering, but Bryson’s major achievement, in my opinion, is the way that he weaves it all together into a narrative that is simultaneously educational and incredibly entertaining. More than once I found myself laughing out loud as he let you in on some of the more obscure – and often absurd – secrets about the quirky personalities of the explorers, scientists, and curious amateurs who made significant (or not so significant) achievements in various fields. But, of course, beyond entertaining you, Bryson teaches you something, as well. After completing the book, I certainly feel more prepared on trivia nights!

Reading the book felt more like sitting next to Bryson and having a friendly chat; his writing style is simply that engaging. Each chapter is only 10-15 pages, and they’re self-encompassing topics. So, you can read one chapter at a time, and not pick the book back up for a week and not have to worry about remembering where you left off. (Between our wedding, our move, and working on my dissertation, it took me over 12 months to finally finish the book – but I think a partial reason it took so long is because I didn’t want it to end!)

The long, overarching narrative that Bryson weaves is fantastic. You certainly are amazed by some of humanity’s achievements (even if they were accidents), but you also are left with a feeling that our present-day situation isn’t preordained. There were so many instances when evolution, politics – human history in general – could have gone any number of different ways. In other words, you’re left with a feeling of humility and appreciation for our world today.

After finishing Bryson’s book, I quickly devoured a short work called The Lena Baker Story, by Lela Bond Phillips. It is an incredibly depressing account about the first and only woman to be executed by the electric chair in the state of Georgia. The book was put out by a local researcher and published by a small company, so it’s not the fanciest history book out there. And perhaps it’s just the historian in me being nit-picky, but I found some of the style choices of the book to be perplexing. For example, when giving direct quotes (from courtroom testimony, for example), Phillips puts them in italics instead of just using quotation marks.

But, such technicalities aside, this is a commendable work of local history that documents the life of Lena Baker, who grew up in a small, rural town in southwest Georgia. Lena had a hard life, from beginning to its early end. She and her family were destitute, she suffered from alcohol addiction, and on top of all that, she was black in the Jim Crow South. When she shoots and kills a white man in self defense, there is no hope for her in the justice system. The jury assigned to her case is made up of white males who were friends of the man killed; Lena’s defense attorney gave a half-hearted attempt to put up a defense, and Phillips suggests that there was even some tampering with the evidence. And readers know from page one that there is no happy ending. Lena Baker was killed by electrocution in Georgia State Prison in the spring of 1945.

I read this book because I grew up in the same town as Lena, so for me, the book was almost personal. I knew the buildings that Phillips described; I can picture the landscapes not from imagination, but from my memories. That’s why the book was so upsetting to me. This wasn’t a general story of systematic racism in a far away Southern town; these were people who walked the same streets as I did. By the story’s end, I’m not sure if I was more angered or saddened. I commend Phillips for attempting to be objective and for not passing judgment. But, I know that if I had written this story, I would have lambasted those involved, from those who were supposed to be enforcing the law to those who masqueraded as defenders of justice: the lawyers and judge who couldn’t even be bothered to put up a good mock trial.

Just as I sat down to begin this post, I Googled “the Lena Baker Story” and found that the book was actually turned into a movie in 2008! After watching a trailer for it, it looks like some of the names of people and places may have been changed, but it seems like it stays pretty true to the book. Now I can’t wait to find it on Netflix or rent it from Amazon. Here’s the preview for the movie…But I also recommend purchasing the short book.

I’ve now started President Jimmy Carter’s memoir about his boyhood: An Hour Before Daylight: Memories of a Rural Boyhood. I picked it to read after The Lena Baker Story because I needed something a little less depressing to read in the morning. I really love “Mista Jimmuh,” and not necessarily because of his politics or his presidency. In all honesty, I haven’t really studied his time in the White House that much, but it seems like he may be a better ex- president than he did a sitting president. Either way, I love what President Carter stands for: peace, compassion, understanding, and education. And while he’s a devout Christian, he’s not one of the judgmental Bible thumpers that I grew up around. He’s intelligent and can grapple with “big picture” issues, but he grew up a poor farmer, so he certainly can understand the everyday man, too. He’s usually calm and level-headed, but not afraid to speak his mind, even when his opinions aren’t popular.

president than he did a sitting president. Either way, I love what President Carter stands for: peace, compassion, understanding, and education. And while he’s a devout Christian, he’s not one of the judgmental Bible thumpers that I grew up around. He’s intelligent and can grapple with “big picture” issues, but he grew up a poor farmer, so he certainly can understand the everyday man, too. He’s usually calm and level-headed, but not afraid to speak his mind, even when his opinions aren’t popular.

I’ve had the pleasure of meeting Pres. Carter when he was back home in Plains, Georgia for a weekend. His home is only about 20 minutes away from our farm, and my family and I even went to church with him. We listened as he taught Sunday School, and his whole message was about compassion. I loved it. So, now I’m excited to read this book and see what helped shape Jimmy Carter into the man he is today.

~*~*~

As I said before, I crack open a novel as I lay in bed at night and let the fantastical worlds take my mind away from the research on the Holocaust. These books, I just read for fun. To be entertained.

I recently read Stephen King’s The Shining. I had never even seen the movie, but I loved the only other King novel I’d read (The Stand), so I thought I’d give The Shining a try. My god, it was truly horrifying! It was probably not a good idea to read that right before trying to go to sleep each night. Nope.

I’m an unabashed fan of the fantasy genre: the more magic, dragons, and imagined worlds there are in the book, the better. Before I read The Shining, I read the first book in Patrick Rothfuss’ “Kingkiller Chronicle” series, The Name of the Wind. It was pretty good, and I especially liked that it’s in the first person. But, honestly, the book didn’t yank my chain, and I don’t think I’ll be finishing the series. It’s no fault of Rothfuss,’ because he’s an excellent writer. I just wasn’t in to the story.

I’m currently reading Of Bone and Thunder by Chris Evans. It is, of course, a fantasy novel, but it’s slightly different than others I’ve read, because Evans was an editor of military historian for decades. So, this story line follows soldiers in an army that is attempting to put down rebellions by some of the subjects in a far away, hot, jungle. Of course, at first the enemy is understood as something sub-human (well, actually, they’re NOT human), but as time goes on, the soldiers enlisted to fight the war realize that they share an awful lot in common with the native “slyts.” Even though they are “the enemy,” they have families, farms, joys. So, it’s an interesting foray into the mindset that warfare cultivates – – – and it’s also awesome that there are fire-breathing dragons and academy-trained wizards.

And, of course I have to give another shout out to my favorite book series of all time (besides Harry Potter, obviously): The Crossroads Trilogy by Kate Elliot. My god, these are three fantastic books. The amount of detail she gives in describing the world that she has created is impressive. You can read my review of the series here.

~*~*~

Okay, that’s all, folks. If any of the brief reviews and recommendations sound interesting, give the books a try! Also, if you’ve got any excellent books that you think I’d enjoy reading, let me know in the comment section below :)

Is this Real Life?

Curious Wanderer? For the past four months, I’ve taken a break from this blog and have been curiously wandering through madness as I work on my dissertation. I’ve set a deadline of #May2016 for the completion of my degree, and essentially that means that I have NO room for error. But, by now my committee has commented on my draft of Chapter One, and I’ve completed a first draft of Chapter Two. So, I feel I’m making good progress.

I’ve had so many opinions on a number of events that’ve occurred recently: the Charleston massacre and the debate over the Confederate flag, Donald Trump’s hilarious entrance into the presidential election, the fact that the Rosetta probe on that far-flung comet woke back up, among many, many others.

But, I’ve had no energy to sit down and write anything now that all day of my every day is spent literally writing history. So, instead, I give you a few memes: #phdlife

Building the First Slavery Museum in America

Below is an article that I found on the New York Times’ website today. It’s written by David Amsden, and the link to the original article can be found here. As a historian studying the process of memorialization and memory-making, I find this Whitney slavery museum to be incredibly fascinating. I’d love to take a field trip down to New Orleans to check it out.

Building the First Slavery Museum in America

By: David Amsden, for the New York Times

John Cummings (right), the Whitney Plantation’s owner and Ibrahima Seck, its director of research, in the Baptist church on the grounds. Credit: Mark Peckmezian for the New York Times.

Louisiana’s River Road runs northwest from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, its two lanes snaking some 100 miles along the Mississippi and through a contradictory stretch of America. Flat and fertile, with oaks webbed in Spanish moss, the landscape stands in defiance of the numerous oil refineries and petrochemichal plants that threaten its natural splendor. In the rust-scabbed towns of clapboard homes, you are reminded that Louisiana is the eighth-poorest state in the nation. Yet in the lush sugar plantations that crop up every couple of miles, you can glimpse the excess that defined the region before the Civil War. Some are still active, with expansive fields yielding 13 million tons of sugar cane a year. Others stand in states of elegant rot. But most conspicuous are those that have been restored for tourists, transporting them into a world of bygone Southern grandeur — one in which mint juleps, manicured gardens and hoop skirts are emphasized over the fact that such grandeur was made possible by the enslavement of black human beings.

On Dec. 7, the Whitney Plantation, in the town of Wallace, 35 miles west of New Orleans, celebrated its opening, and it was clear, based on the crowd entering the freshly painted gates, that the plantation intended to provide a different experience from those of its neighbors. Roughly half of the visitors were black, for starters, an anomaly on plantation tours in the Deep South. And while there were plenty of genteel New Orleanians eager for a peek at the antiques inside the property’s Creole mansion, they were outnumbered by professors, historians, preservationists, artists, graduate students, gospel singers and men and women from Senegal dressed in traditional West African garb: flowing boubous of intricate embroidery and bright, saturated colors. If opinions on the restoration varied, visitors were in agreement that they had never seen anything quite like it. Built largely in secret and under decidedly unorthodox circumstances, the Whitney had been turned into a museum dedicated to telling the story of slavery — the first of its kind in the United States.

The Whitney Plantation’s “Big House” in January 2015. Credit: Mark Peckmezian for the New York Times

Located on land where slaves worked for more than a century, in a state where the sight of the Confederate flag is not uncommon, the results are both educational and visceral. An exhibit on the North American slave trade inside the visitors’ center, for instance, is lent particular resonance by its proximity, just a few steps away outside its door, to seven cabins that once housed slaves. From their weathered cypress frames, a dusty path, lined with hulking iron kettles that were used by slaves to boil sugar cane, leads to a grassy clearing dominated by a slave jail — an approach designed so that a visitor’s most memorable glimpse of the white shutters and stately columns of the property’s 220-year-old “Big House” will come through the rusted bars of the squat, rectangular cell. A number of memorials also dot the grounds, including a series of angled granite walls engraved with the names of the 107,000 slaves who spent their lives in Louisiana before 1820. Inspired by Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, the memorial lists the names nonalphabetically to mirror the confusion and chaos that defined a slave’s life.

Ibrahima Seck, the Whitney’s director of research, at a memorial on the plantation. Credit: Mark Peckmezian for the New York Times

Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans, was among those to address the crowd on opening day. He first visited the Whitney as the state’s lieutenant governor in 2008, when the project was in its infancy, and at the time he compared its significance to that of Auschwitz. Now he was speaking four days after a grand jury in New York City declined to indict a police officer in the chokehold death of Eric Garner, a black man who was stopped for selling untaxed cigarettes; 13 days after another grand jury in Missouri cleared an officer in the shooting death of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager; and two weeks after Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old black boy playing with a toy gun in a Cleveland park, was killed by a police officer. Evoking the riots and protests then gripping the nation, Landrieu said, “It is fortuitous that we come here today to stand on the very soil that gives lie to the protestations that we have made, and forces us as Americans to check where we’ve been and where we are going.”

The mayor concluded his speech by extending his hand to an older man standing just offstage to his left. Stocky and bespectacled, with a thick head of unkempt white hair, John Cummings was as much a topic of conversation among those gathered as the Whitney itself. For reasons almost everyone was at a loss to explain, he had spent the last 15 years and more than $8 million of his personal fortune on a museum that he had no obvious qualifications to assemble.

The Whitney Plantation’s “Big House” in 1926. Credit: Robert Tebbs/The Collections of the Louisiana State Museum

“Like everyone else,” John Cummings said a few days earlier, “you’re probably wondering what the rich white boy has been up to out here.”

He was driving around the Whitney in his Ford S.U.V., making sure the museum would be ready for the public. Born and raised in New Orleans, Cummings is as rife with contrasts as the land that surrounds his plantation. He is 77 but projects the unrelenting angst of a teenager. His disposition is exceedingly proper — the portly carriage, the trimmed white beard, the florid drawl — but he dresses in a rumpled manner that suggests a morning habit of mistaking the laundry hamper for the dresser. As someone who had to hitchhike to high school and remains bitter about not being able to afford his class ring, he embodies the scrappiness of the Irish Catholics who flooded New Orleans in the 19th century. But as a trial lawyer who has helped win more than $5 billion in class-action settlements and a real estate magnate whose holdings have multiplied his wealth many times over, Cummings personifies the affluence and power held by an elite and mostly white sliver of a city with a majority black population.

“I suppose it is a suspicious thing, what I’ve gone and done with the joint,” he continued, acknowledging that his decision to “spend millions I have no interest in getting back” on the museum has long been a source of local confusion. More than a few of the 670 residents of Wallace — 90 percent of whom are black, many the descendants of slaves and sharecroppers who worked the region’s land — have voiced their bewilderment over the years. So, too, have the owners of other tourist-oriented plantations, all of whom are white. Members of Cummings’s close-knit family (he has eight children by two wives) also struggle to clarify their patriarch’s motivations, resorting to the shoulder-shrugging logic of “John being John,” as if explaining a stubborn refusal to throw away old newspapers rather than a consuming, heterodox and very expensive attempt to confront the darkest period of American history. “Challenge me, fight me on it,” he said. “I’ve been asked all the questions. About white guilt this and that. About the honky trying to profit off of slavery. But here’s the thing: Don’t you think the story of slavery is important?” With that, Cummings went silent, something he does with unsettling frequency in conversation.

“Well, I checked into it, and I heard you weren’t telling it,” he finally resumed, “so I figured I might as well get started.”

This was a practiced line, but also an earnest form of self-indictment: Cummings’s way of admitting his own ignorance on the subject of slavery and its legacy, and by extension encouraging visitors to confront their own. As with the rest of his real estate portfolio, which includes miles of raw countryside and swampland, a 12-story luxury hotel near the French Quarter, a cattle farm in rural Mississippi and a 1,200-acre ranch in West Texas that he has never set foot on, he initially gravitated toward the Whitney simply because it was for sale. (“Whatever Uncle Sam and the bartender let me keep,” he likes to note, “I bought real estate with it.”) Originally built by the Haydel family, a prosperous clan of German immigrants who ran the property from 1752 to 1867, the grounds had been uninhabited for a quarter century. “I knew I wasn’t going to live here,” Cummings said as he drove past the blacksmith’s shop that he spent $300,000 rebuilding, where a plaque noted that a slave named Robin worked on the plantation for 40 years and where the actor Jamie Foxx, playing a slave in “Django Unchained,” was filmed being branded. “But aside from that, I didn’t know what I would do with the place.”

It takes just a few minutes of conversation with Cummings, however, to understand that he would never have been keen on restoring the Whitney in the mold of neighboring plantations, which rely on weddings and sorority reunions to supplement the income brought in by picnicking tourists. Pet projects he has taken up in recent years include outlining for the Vatican a list of wrongs the Catholic Church should formally apologize for and — to the chagrin of, in his words, “my friends who have all had political sex changes in the past 15 years” — exploring ways to curb the influence of conservative “super PACs.” Decades ago, his interest in abuses of power led to his involvement in the civil rights movement; in 1968, he worked alongside African-American activists to get the Audubon Park swimming pool in New Orleans opened to blacks. “If someone is going to deny someone rights simply because they have the power to do it — well, I’m interested,” he explained. “I’m coming, and I’m going to bring the cannons.”

Still, his plans for the Whitney might have gone in an entirely different direction, if not for the existence of an unlikely document. The property’s previous owner was Formosa, a plastics and petrochemical giant, which in 1991 planned to build a $700 million plant for manufacturing rayon on its nearly 2,000 acres. Preservationists and environmentalists balked. Looking for avenues of appeasement, Formosa commissioned an exhaustive survey of the grounds, with the idea that the most historic sections would be turned into a token museum of Creole culture while a majority of the rest would be razed to make way for the factory. In the end, it was wasted money and effort: The opposition remained vigilant, rayon was going out of fashion, the Whitney went back on the market and Cummings inherited the eight-volume study with the purchase. “Thanks to Formosa, I knew more about my plantation than anyone else around here — maybe more than any plantation in America outside of Monticello,” said Cummings, a litigator accustomed to teasing secrets from dense paperwork. “A lot of what was in there was about the architecture and artifacts, but you started to see the story of slavery. You saw it in terms of who built what.”

After digesting the study, Cummings began readying “any book I could find” about slavery. Particularly influential was Africans in Colonial Louisiana, by Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, a professor at Rutgers. Certain details startled Cummings, like the fact that 38 percent of slaves shipped from Africa ended up in Brazil. No wonder, he thought, that the women he watched on television celebrating Carnival in Rio de Janeiro so closely resembled those he saw dancing in the Mardi Gras parades that surrounded him as a youth. “I started to see slavery and the hangover from slavery everywhere I looked,” he said. As a descendant of Irish laborers, he has no direct ties to slaveholders; still, in a departure from the views held by many Southern whites, Cummings considered the issue a personal one. “If ‘guilt’ is the best word to sue, then yes, I feel guilt,” he said. “I mean, you start understanding that the wealth of this part of the world – wealth that has benefited me – was created by some half a million black people who just passed us by. How is it that we don’t acknowledge this?”

Cummings steered the vehicle past the yellow fronds of banana trees and pulled to a stop in front of a sculpture, a black angel embracing a dead infant, the centerpiece of a memorial honoring the 2,200 enslaved children who died in the parish in the 40 years leading up to the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863. At traditional museums, such memorials come to fruition only after a lengthy process — proposals by artists, debates among the board members, the securing of funds. This statue, though, like everything on the property, began as a vision in Cummings’s mind and became a reality shortly after he pulled out his checkbook. Perhaps most remarkable is that this unconventional model has yielded conventionally effective results: at once chastening and challenging, beautiful and haunting. “Everything about the way the place came together says that it shouldn’t work,” says Laura Rosanne Adderley, a Tulane history professor specializing in slavery who has visited the Whitney twice since it opened. “And yet for the most part it does, superbly and even radically. Like Maya Lin’s memorial, the Whitney has figured out a way to mourn those we as a society are often reluctant to mourn.”

Before leaving the grounds, Cummings stopped at the edge of the property’s small lagoon. It was here that the Whitney’s most provocative memorial would soon be completed, one dedicated to the victims of the German Coast Uprising, an event rarely mentioned in American history books. In January 1811, at least 125 slaves walked off their plantations and, dressed in makeshift military garb, began marching in revolt along River Road toward New Orleans. (The area was then called the German Coast for the high number of German immigrants, like the Haydels.) The slaves were suppressed by militias after two days, with about 95 killed, some during fighting and some after the show trials that followed. As a warning to other slaves, dozens were decapitated, their heads placed on spikes along River Road and in what is now Jackson Square in the French Quarter.

“It’ll be optional, O.K.? Not for the kids,” said Cummings, who commissioned Woodrow Nash, an African-American sculptor he met at Jazz Fest, to make 60 heads out of ceramic, which will be set atop stainless-steel rods on the lagoon’s small island. “But just in case you’re worried about people getting distracted by the pretty house over there, the last thing you’ll see before leaving here will be 60 beheaded slaves.”

The memorial had lately become a source of controversy among locals, who were concerned that it would be too disturbing.

“It is disturbing,” Cummings said as he pulled out past Whitney’s gate. “But you know what else? It happened. It happened right here on this road.”

John Cummings brought these cabins from another plantation to replace the ones at the Whitney, which were destroyed in the 1970s. Credit: Mark Peckmezian for the New York Times

A nation builds museums to understand its own history and to have its history understood by others, to create a common space and language to address collectively what is too difficult to process individually. Forty-eight years after World War II, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum opened in Washington. A museum dedicated to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks opened its doors in Lower Manhattan less than 13 years after they occurred. One hundred and fifty years after the end of the Civil War, however, no federally funded museum dedicated to slavery exists, no monument honoring America’s slaves. “It’s something I bring up all the time in my lectures,” says Eric Foner, a Columbia University historian and the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning “Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery.” “If the Germans built a museum dedicated to American slavery before one about their own Holocaust, you’d think they were trying to hide something. As Americans, we haven’t yet figured out how to come to terms with slavery. To some, it’s ancient history. To others, it’s history that isn’t quite history.”

These competing perceptions converge with baroque vividness in the South. The State of Mississippi did not acknowledge the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery until 1995 and formally ratified it only in 2013, when a resident was moved to galvanize lawmakers after watching Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln.” While some Southern states have passed resolutions apologizing for slavery in the last decade, a majority, Louisiana among them, have not. In 1996, when Representative Steve Scalise, now the third-highest-ranking Republican in the House, was serving in the Louisiana State Legislature, he voted against such a bill. “Why are you asking me to apologize for something I didn’t do and had no part of?” he remarked at the time. This episode recently came to light amid the revelation that in 2002 he addressed a gathering of white supremacists at a conference organized by David Duke, formerly the grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, an organization founded the year the Civil War ended.

Slavery is by no means unmemorialized in American museums, though the subject tends to be lumped in more broadly with African-American history. In 2004, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center opened in Cincinnati with the mission of showcasing “freedom’s heroes.” Since 2007, the Old Slave Mart in Charleston, S.C., has operated as a small museum focusing on the early slave trade, on a site where slaves were sold at public auctions until 1863. The National Civil Rights Museum, which opened in Memphis in 1991 and was built around the Lorraine Motel, where the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, offers a brief section devoted to slavery. Next year, the National Museum of African American History and Culture is scheduled to be dedicated in Washington as part of the Smithsonian Institution, a project supported by $250 million in federal funding; exhibits on slavery will stand alongside those containing a trumpet played by Louis Armstrong and boxing gloves worn by Muhammad Ali. “It has to be said that the end note in most of these museums is that civil rights triumphs and America is wonderful,” says Paul Finkelman, a historian who focuses on slavery and the law. “We are a nation that has always readily embraced the good of the past and discarded the bad. This does not always lead to the most productive of dialogues on matters that deserve and require them.”

What makes slavery so difficult to think about, from the vantage point of history, is that it was both at odds with America’s founding values — freedom, liberty, democracy — and critical to how they flourished. The Declaration of Independence proclaiming that “all men are created equal” was drafted by men who were afforded the time to debate its language because the land that enriched many of them was tended to by slaves. The White House and the Capitol were built, in part, by slaves. The economy of early America, responsible for the nation’s swift rise and sustained power, would not have been possible without slavery. But the country’s longstanding culture of racism and racial tensions — from the lynchings of the Jim Crow-era South to the discriminatory housing policies of the North to the treatment of blacks by the police today — is deeply rooted in slavery as well. “Slavery gets understood as a kind of prehistory to freedom rather than what it really is: the foundation for a country where white supremacy was predicated upon African-American exploitation,” says Walter Johnson, a Harvard professor. “This is still, in many respects, the America of 2015.”

In 2001, Douglas Wilder, a former governor of Virginia and the first elected black governor in the nation, announced his intention to build a museum that would be the first to give slavery its proper due — not as a piece of Southern or African-American history but as essential to understanding American history in general. Christened the United States National Slavery Museum, it was to be built on 38 acres along the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, Va. Wilder, the grandson of slaves, commissioned C. C. Pei, a son of I. M. Pei, to design the main building, which would be complemented by a full-scale replica of a slave ship. A number of prominent African-Americans, including Bill Cosby, pledged millions of dollars in support at black-tie fund-raisers. The ambition that surrounded the project’s inception, however, was soon eclipsed by years of pitfalls. By 2008, there were not enough donations to pay property taxes, let alone begin construction; in 2011, the nonprofit organization in charge of the project filed for bankruptcy protection. As it happens, it was during the same period Wilder’s project unraveled that John Cummings, unburdened by any bureaucracies, was well on his way to completing a slavery museum of his own.

Cummings and Seck at one of many memorials to slaves on the plantation.

Cummings and Seck at one of many memorials to slaves on the plantation.Credit: Mark Peckmezian for The New York Times

For much of the last 13 years, Cummings has been joined on the Whitney’s grounds by a Senegalese scholar named Ibrahima Seck. A 54-year-old of imposing height, Seck first met Cummings in 2000, when Seck, who has made regular trips to the South since winning a Fulbright in 1995, attended a talk at Tulane with Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, the Rutgers professor. Cummings put up Seck at the International House, the hotel he owns in downtown New Orleans, and invited him to see the Whitney. Though at that point it was little more than a series of decrepit buildings entangled in feral vegetation, Seck was impressed that Cummings was thinking about it exclusively within the context of slavery. As someone from the region of Africa that provided more than 60 percent of Louisiana’s slaves, he was disturbed by the way other plantations romanticized the lives of the white owners, with scant mention of the enslaved blacks who harvested the land and built the grand homes fawned over by tourists. After walking the property with Seck for a few hours, Cummings invited him to return to New Orleans the next year to help crystallize the Whitney’s mission. Seck took him up on the offer, and for the next decade, Cummings flew Seck in from Africa each year during the scholar’s summer vacation.

Since 2012, Seck has lived full time in New Orleans to serve as the director of research for the Whitney. “As historians, we do the research and we write dissertations and we go to conferences, but very little of the knowledge gets out,” Seck said one afternoon in his French-inflected baritone while seated on the antique upholstered sofa in the parlor of the property’s Big House. “That’s why a place like this is so important. Not everyone is willing to read nowadays, but this is an open book.” He took a moment to glance around the lavish room, its hand-painted ceiling now meticulously restored. “Every day I think about how remarkable this is,” Seck said. “One hundred and fifty years ago, I would not be able to do what I’m doing here now. I would have been a slave.”

The alliance between the two men has been an auspicious one, with Seck’s patience and expertise serving as a counterbalance to the instinctual eccentricity of Cummings. While Seck researched the Whitney’s history, Cummings became something of a hoarder, buying anything he thought might one day be relevant to the project. When he learned about a dilapidated Baptist church in a neighboring parish that was founded by freed slaves in 1867, for example, he brought it across the Mississippi and had it restored on the grounds at a cost of $300,000. When recordings of interviews with former slaves that were made in the 1930s as part of the W.P.A.’s Federal Writers’ Project were acquired, Cummings hired a son-in-law who works as a sound engineer in Hollywood to clean them up; he plans to install a speaker system near the slave cabins, where the recordings will play on a loop, allowing visitors to hear the voices of former slaves while staring into the type of homes in which they once lived. After Seck unearthed in old court documents the names of 354 slaves who worked on the land before emancipation, Cummings bought an engraving machine so they could be etched in Italian granite in a memorial he christened the “Wall of Honor.”

“By 2005, it was clear to me that we were building a museum, but I’m not sure John was thinking about it in those terms,” Seck said. “If John feels something, he just goes ahead and does it. His stubbornness can be frustrating, but who in the world is willing to put so many millions of dollars into a project like this? If you find one, you have to support it.”

In his years of working on the Whitney, Seck has come to see the museum as both a memorializing of history and a slyly radical gesture: Cummings’s desire to shift the consciousness of others as his own has been altered, and in the process try to make amends of a kind that have been a source of debate since emancipation.

“If one word comes to mind to summarize what is in John’s head in doing this,” Seck said, “that word would be ‘reparations.’ Real reparations. He feels there is something to be done in this country to make changes.”

In 1835, a biracial child named Victor was born on the grounds of the Whitney, the son of a slave named Anna and Antoine Haydel, the brother of Marie Azelie Haydel, the slaveholder who ran the plantation at the time. One hundred and seventy-nine years later, a group of both the black and white descendants of the Haydels made their way to the Whitney’s opening in December. Many were meeting for the first time, and the sight of them embracing and marveling at the similarities in their appearances was as powerful as any memorial on the plantation. Among the black Haydels in attendance was one of Victor’s great-grandchildren, Sybil Haydel Morial, a well-known local activist who is the widow of Ernest Morial, the first black mayor of New Orleans, and the mother of Marc Morial, a subsequent mayor. “I was with John when he helped get the pool in Audubon Park opened to blacks,” she said in a later conversation. “Now, with the Whitney, he has given us a place where we can come and clear the air. If my slave great-grandfather had lived eight more years, I would have known him. Yet growing up, whenever my elders talked about slavery, they’d always get quiet when we kids were near.” Morial added that she hoped “some people around here may find their views changing” after visiting the Whitney, which seemed to be the case with some of her white relatives at the opening.

“I have to say, I was a little offended when I heard that slavery, of all the stories, was going to be the focus,” Glynne Couvillion, a white Haydel, said while standing inside the Baptist church, surrounded by dozens of ghostly sculptures of child slaves that Cummings commissioned to represent those interviewed by the Federal Writers’ Project as they would have looked when enslaved. “But after today, I’m just in awe and proud to be connected to this place.”

For all the time and money Cummings has dedicated to the Whitney — and he is by no means finished, with plans to build an adjacent institute for the study of slavery — the museum was built on a shoestring budget compared with traditionally financed institutions. (The Holocaust Memorial Museum cost about $168 million.) Besides Seck, there were only two full-time staff members, an energetic young woman named Ashley Rogers, who serves as the director, and her deputy, Monique Johnson, a descendant of sharecroppers from the area, and it was evident that they were still finding their footing. Like the other plantations along River Road, the Whitney can be seen only through a guided tour — the cost is $22 — and a number of the docents struggled to find the proper tone. (“Time to depress you a little more,” one could be heard saying at various points.) Others struggled to answer questions about how, exactly, sugar cane was harvested by slaves, responding instead with generalities intended to incite emotion rather than educate: “It was the hardest, most grueling slave work imaginable.”

Yet this awkwardness might well serve as one of the Whitney’s strengths. Talking about slavery and race is awkward, and the museum stands a chance of becoming the rare place where this discomfort can be embraced, and where the dynamic among the mainly mixed-race tours can offer an ancillary form of education. A man who grew up in a “maroon community,” as bayou enclaves founded by runaway slaves are known, was so moved during his tour that he volunteered to work as a guide. A young black woman mentioned that she avoided tours at another nearby plantation because an ancestor was lynched on the grounds. Among the Whitney’s first visitors was a black man named Paul Brown, whose father was a field hand and who arrived dressed in a sharp blazer and a fedora on opening day “to shake the man’s hand who made this place possible.” During his tour, he offered personal anecdotes that served to buttress the white guide’s skittishness — bringing the past into the present, for instance, by pointing out how the images of slaves etched in one memorial were reminiscent of portraits of his ancestors. “I wish some of my white co-workers would come to this place,” he said afterward. “They’d understand me in ways they’ve failed for 30 years.”

Jonathan Holloway, a dean at Yale College and a professor of African-American studies, arrived for a tour in late January. He was in the area to give a talk at Louisiana State University about the ways the horrors of slavery are confronted and avoided in heritage tourism, and he found the Whitney to be a “genius step” in a long-overdue direction. “People have tried to do a museum like this for years, and I’m still stunned that this guy made it happen,” he said afterward. “There I was, coming down to talk about how in trying to tell the story, it’s often one step forward and two steps back, and boom, here’s the Whitney.” Holloway was particularly taken by the museum’s subversive approach. “Having been on a number of tours where the entire focus is on the Big House, the way they’ve turned the script inside out is a brilliant slipping of the skirt,” he said. “The mad genius of the whole thing is really resonant. Is it an art gallery? A plantation tour? A museum? It’s almost this astonishing piece of performance art, and as great art does, it makes you stop and wonder.”

Cummings, for his part, has been on the grounds every day since the Whitney opened, where he is in the habit of approaching visitors as they enter and telling them how they should feel afterward: “You’re not going to be the same person when you leave here” — a line that some found more grating than endearing. Inwardly, though, he was constantly making notes on what could be done to improve the experience.

“Look, we’re not perfect, and we’ve made a lot of mistakes, and we’ll make more,” he said one afternoon as the sun set across the sugar-cane fields that surround the plantation in much the form they did when slaves worked them 200 years ago. “We need all the help we can get — not financial, but we need brains.” With this in mind, he recently started reaching out to prominent African-American academics, hoping to create a board of directors — typically the first step for a museum, not one taken six weeks after opening day. “I’m firing before I’m aiming, O.K.?” he said. “I’m smart enough to know I don’t have the answers, but so far it looks like it’s the right thing.”

Cummings and Seck in one of the cabins. Credit: Mark Peckmezian for the New York Times.

An earlier version of this article misidentified the source of the phrase “all men are created equal.” It is from the Declaration of Independence, not the Constitution.

The Construction of Queer Memory: Media Coverage of Stonewall 25

Avila-Saavedra, Guillermo. “The Construction of Queer Memory: Media Coverage of Stonewall 25.” Unpublished paper delivered at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication conference, San Francisco, August 2006. Accessible here.

Subject: An examination of the role of media in the shaping of the role of the Stonewall riots in the gay collective memory.

Main Points: The author studies the media attention given to “Stonewall 25,” the 1994 celebration of the 25th anniversary of the NYC Stonewall riots. It’s an interesting paper that deals with collective memory, collective identity, and heritage building. So, he spends some time spelling out his theoretical approach/understanding of the concepts of memory and identity formation. He then specifically focuses on the media’s role in shaping a specific Stonewall narrative. He argues that “the media are complicit in shaping a memory of Stonewall that reflects the political goals of the American queer movement in the 1990s.”

This narrative portrayed by Stonewall 25 organizers and the media was one that portrayed the gay community as a diverse, but ultimately singular or united community. In this sense, the “unity through diversity” discourse was forced back onto the 1969 riots themselves. In none of the New York Times articles or Stonewall documentaries that appeared for the 25th anniversary was it mentioned that the Stonewall Inn was primarily a hangout for drag queens, transvestites, and gays and lesbians of color; in other words, it was a place for individuals who did not fit into the white, middle class, male gay culture that was dominant at the time. But as Avila-Saavedra demonstrates, all of the media for the 1994 anniversary rewrote history and portrayed the Stonewall Riots as a coming together of diverse peoples, gays and lesbians of all walks of life united in their ‘gayness.’

Even the reporting of the Stonewall 25 events themselves were portrayed in a particular way. Reporters focused on the celebration of diversity and unity of queer America, overlooking the fact that a large fissure had emerged during the planning of the parade and events. The Stonewall Veterans Association, members of NY ACT UP, and other more radical activists protested that the radical and revolutionary origins of the gay liberation movement (and the Riots themselves) were being purposefully ignored, in place of a “Eurocentric,” assimilationist, middle class definition of “gay.” One newspaper did report that the radical groups had been left out of Stonewall 25, and that “the spirit of the riots had been lost on a celebration of middle-class assimilation dream with its patriarchal and racial components intact” (7). Few media outlets reported that these protesters decided to have their own parade, or when it was reported, the media focused instead on the fact that, at the end, the two parades merged together in a display of harmony. Therefore, Avila-Saavedra claims that the media reports of Stonewall 25 not only commemorated the Stonewall riots, but helped turn them into a myth as well, a myth that was useful for the LGBT politics of the 1990s (coming out, lobbying for rights like marriage, etc.).

To back up such claims, Avila-Saavedra looks at several media outlets. The New York Times, he shows, ran completely uncritical accounts of the Stonewall riots, displaying them in a Whiggish, progressive account of triumph, leaving out all of the people who did not fit into this coherent story. The Village Voice, an alternative newsweekly published from NYC’s Greenwich Village, on the other hand, gave more attention to the radicals’ protests of the Stonewall 25 celebrations. Moreover, the Village Voice published interviews with witnesses of the Stonewall riot that challenged the neat and tidy narrative being told by gay rights leaders. Therefore, “the coverage in the Village Voice is less concerned with consensus.” The Advocate focused not on the significance of Stonewall riots, the meaning of which was taken for granted, but instead focused on the forms of celebration by questioning whether parades and concerts can adequately commemorate such momentous events. The Advocate article “fails to voice dissenting memories and interpretations of the riots and implicitly endorses their mythical significance” (8). He then analyzes how Stonewall was portrayed on TV through the PBS special “Out Rage 69,” the official Stonewall 25 documentary “Stonewall 25: The Future is Ours,” and ends with a description of the Stonewall movie, produced by Nigel Finch. All of these, Avila-Saavedra shows, present an uncritical reproduction of the Stonewall Myth that has been circulated and then commemorated by the celebrations of 1994.

My Comments: This is a really fascinating paper, and it deals with a lot of the same themes that my own research will. I like its focus on the media in forming collective memories. In particular, the paper reveals the legitimizing nature of the American media. “This obsession with media attention is exemplary of the queer movement’s search for legitimization through one of the most ubiquitous institutions in American culture. It did not happen if it was not on TV.” So, these types of events are a part of what David Lowenthal would call heritage formation – fashioning a past that is useful for the present. But, like this paper shows, such endeavors – especially ones that focus on unity and singular narratives – often leave people out.

For more books on the history of gay rights, sexuality, and gender, see my full list of book reviews.