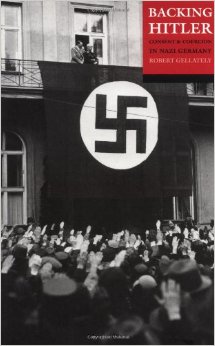

Gellately, Robert. Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

In Backing Hitler, Gellately completely reevaluates the role that the German population played in the establishment and maintenance of the Nazi dictatorship. Moreover, he seeks to answer the problematic question of just how much the Germans knew of the Nazis’ more heinous policies. He provocatively argues that not only did most Germans know that their country had a Secret Police and a concentration camp system, but that they supported (or at least took pride in) the government’s heavy-handed war against those “who were regarded as ‘outsiders,’ ‘asocials,’ ‘useless eaters,’ or ‘criminals’” (vii). The Nazi regime that emerges from Gellately’s story is not one that enforced uniform terror on everyone with no regard for popular opinion; instead, we learn of a state obsessed with finding out what its “Aryan” people thought of it. Consequently, the Third Reich was as dependent on the Volk’s consent to function as it was on forced coercion.

Central to Gellately’s argument is the observation that “Hitler wanted to create a dictatorship, but he also wanted the support of the people” (1). Therefore, Nazi leaders had to keep the Aryan core of the utopian Volksgemeinschaft in mind when establishing the networks of state power. In order to tap into the power of the people, Nazis capitalized on the widespread desire to return to a more stable, traditional German society, a society that the liberal, democratic Weimar Republic had destroyed. The Nazis, then, did not try to hide the fact that they used violence and coercion in dealing with their enemies (portrayed as enemies of the German people). Initially, Communists were targeted, arrested, and thrown into the new network of concentration camps. What may be surprising to readers is the fact that these concentration camps were not kept a secret either. The opening of the famous Dachau concentration camp in 1933, for example, was announced with front-page headlines (51). Gellately argues that even if Germans did not agree with the stories of excessive violence associated with the concentration camps, they did not protest because “most of the coercion and terror was used against…social groups for whom the people had little sympathy” (2).

Gellately traces distinct phases of consent for Hitler and Nazism. The first phase was when the Nazi government was able to provide tangible results: a recovered economy and a drop in the crime rate (1933-1938). The second phase began with the start of the war and lasted until 1944, and was one in which Germans increasingly consented to the implementation of “police justice,” or the ‘preventative’ use of force against even potential criminals, outside of the jurisdiction of the courts. During this time, the concentration camp inmates became an integral part of daily life as they were marched to and from factories to work for the German war effort.

The book is most concerned with the level of popular knowledge of and consent for the Nazis’ violent and authoritarian methods. Gellately concludes that the regime made sure its secret police wasn’t much of a secret at all. The media was used not as a way to simply “brainwash” Germans, but to present the regime’s violence as taking a firm stance against crime and undesirables, thus forging a harmonious “racial community of the people.” The Nazi surveillance state encouraged citizens to join the cause and denounce anyone who was an enemy of the people. In fact, 50% of all recorded denunciations came from everyday citizens, even if the motives for these denunciations were selfish. In conclusion, Gellately states, “On balance, the coercive practices, the repression, and persecution won far more support for the dictatorship than they lost” (259).

For more books on modern German history, see my full list of book reviews here.