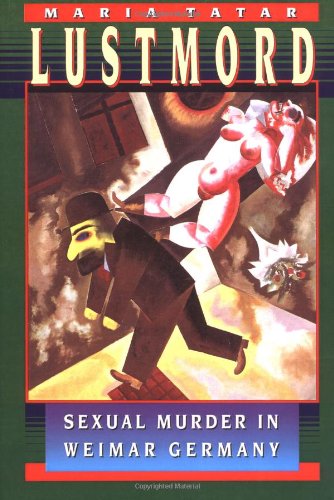

Tatar, Maria. Lustmord: Sexual Murder in Weimar Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995.

In her short but dense book, Tatar examines the role of Lustmord (sexual murder) in Germany during the Weimar period. She reveals that violent murders of women took a central place in this era. The media chronicled – in often grizzly detail – the acts of serial killers and the subsequent trials of the murders. Tatar goes beyond actual murders to show that the mutilated bodies of women cropped up as the subjects of many works of art in several genres: canvases, novels, and on the screen. What can we make of all this violence? What does it mean that the victims were always women? These are the questions that Tatar tackles in her provocative work.

First, Tatar focuses on a number of real-life serial murderers that dominated the German headlines in the 1920s. The cases of Fritz Haarmann, Wilhelm Grossmann, Karl Denke, and Peter Kürten reveal how the media and public reacted to the existence of such violent murderers (whose victims were always women or children). Tatar explains the public’s frenzied reaction to the murders and the simultaneous “pathologization” of criminality (56). “The population at large was thus seen as duplicating the psychosis of the murderer, partaking of his sexualized frenzy in its desperate attempt to defuse the general sense of anxiety by finding scapegoats” (46). The press contributed to this frenzy by boosting the “toxic” effect of killer and giving them the attention they wanted. Moreover, the attention provided incentive for copy-cat killers (47).

Tatar’s analysis of particular novels, paintings, and movies is interesting, particularly for someone interested in art or cultural history of the Weimar Republic. But what I find more interesting, convincing, and ultimately useful is her discussion of perpetrators and victims. One of the main threads throughout the book is her claim that in cases of real or fictional Lustmord, the perpetrator (artist/murderer) often transitions into victim by the end. This is only understandable within the larger context of modern German culture. Tatar argues that a flux of hostile female images in art “gives vivid testimony to an unprecedented dread of female sexuality and its homicidal power” (10). World War One had destroyed the traditional social order: it redrew national boundaries, destroyed the earth in the trenches, maimed bodies, and also transformed mores. Men, Tatar argues, saw the emancipation of women, as a devastating event. There was a short step from the sexual empowerment of the femme fatale to her overstepping her bounds and destabilizing society (11). Therefore, portraying women as the causes of social disorder allowed for her murder to become an act of self-defense or sacrifice. “The murderous agent takes on the role of victim, who has sacrificed his life by killing” (172). This act of turning the aggressor into victim through sacrifice (Tatar notes that in German Opfer means both victim and sacrifice) was also used in the racial demonization of the Jews in Nazi Germany. In both cases, repression and projection operate in such a way as to turn the target of murderous violence into a peril of monstrous proportions, one that threatens to sap the lifeblood of the “victims” and thereby authorizes a form of unrestrained retaliatory violence marked by frenzied excess” (152).

Through this process of demonization of the Other and transformation from aggressor to victim, Tatar draws an important connection between Lustmord culture in the Weimar era to the policies of the Third Reich. Moreover, she shows the importance of the Great War in shaping this murderous view of women (and “the other”). In doing that, Tatar reveals that Weimar can’t be seen as a “glamorized…period of alluring decadence” between two dark periods of German history. Instead, it is a bridge between the two world wars.

Tatar’s book is interesting and provocative, but I am left with several questions, the main one being: What about women artists in the Weimar era? How did they feel about these Lustmord paintings? Did they make paintings in which men’s bodies were mutilated?

For more books on modern German history, see my full list of book reviews.